“The bigger they are the harder they fall” seems to be completely unrelated to this, but after filling out the number of accident reports I have over the years, I think somehow this does seem to matter. Every occurrence relates to what I was first told in my final interview upon hiring, and in my classroom training during the discussion on accidents and writing the accident report. It is the only class that has stood out in my mind over the years; and was a very clear take on what this job meant as a part of our larger economy, and was so right to the core that even through challenging contract negotiations over the years with our union and management, and even with public comment in the news, these words still, to me, ring true.

This was during the mid to late nineties when Netscape was the Godsend, and Yahoo was unstoppable. “Yes, they have great stock options and a creative workspace, but what they don’t have is your longevity at one job.” And other senior operators in various classes at the training department, and even in the Gilley room, have echoed this sentiment in a slightly different way with the simple encouragement to, “Stick around and see how it goes.” My favorite is, “Sit Back and Watch the Show!”

I identified with this on a deep level, and I am glad I did. No matter how hard this job was to be, no matter how awful I thought it was, was to persevere and keep at it. And sure enough, just like any other job, I started to see the repeats. The patterns of the same thing happening over and over, and how to deal with whatever, became a natural working part of my mind.

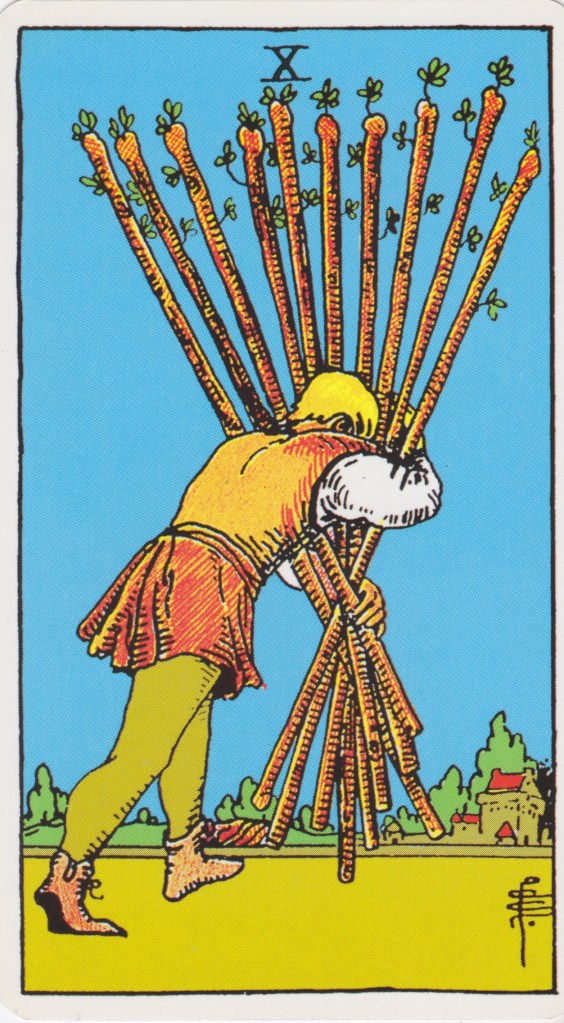

This one trait I have learned from my Grandfather who was up early every day to commute in to New York City to work for Con Edison, from my Dad behind his desk in the study to prepare another grant request to the National Institute of Health, and from Wilton who got up at 5 a.m. to work in the shipyards at Newport News: keep on trudging. All these men had something in common: they never received any accolades or promotion for their steady paced work, but they kept at the same job for all of their life.

And that steady paycheck was something I never really had, with like 8 W-2s during I think it was 1978, or the five I had in 1987! My heart goes out to any young person struggling in their teens or twenties who doesn’t see the benefit and simplicity of keeping to the grindstone for a period of time like years instead of months. The fallacy of cut and run, whereby I quickly grasp a job description, and then move on, was not the real truth. Overcoming challenges and seeing them through were actually more important for long range skills in developing intimacy with others.

To be sure, I also envy the youth aspect of trying different things, but at some point, I realized my life could be simpler if I just kept to one thing at a time, and gave it more time than I thought I should. Walking off a job in 40 minutes or after one day, seemed to be more of my modus operandi, than to wade through difficulty and ask for help. If I could have just waited it out to get a few suggestions on how to break down a task into smaller parts to see past the other side of failure. If any sidebar to this chapter exists, it would have to be to put young brashness aside to get feedback about what has worked in the past for others. And the cost of this simple action, to ask for help, which is to say, to not ask for help, has probably been the largest missed opportunity cost in my life which could have saved me lots of grief.

To get back to the training class, I vividly remember our instructor’s first question to our group of cadets, if you will, freshly being minted by the city to become a transit operator. The instructor asked, “What is the first thing I have read time and time again on accident reports, or heard from an operator in a conversation about and accident?” And what confuses me and has left me completely confounded year after year, even though I piped up with the correct answer as soon as he asked it, was the lack of simplicity and clarity I possessed in writing out my reports. I always wondered why it took so long for the division trainer to grade my report. Now, I get my answer about an accident within a day or two from the accident. And I could not see why other operators knew why this was happening, and why they got their verdicts so much quicker than I did. And I have been teased and mocked to almost no end about the War and Peace, or Gone With The Wind, lengthy essays on my reports. I talk too long and I write too much, and my only surmise is because I am too much a thinker, and spend too much time in my head. I guess it’s why I am enjoying this book so much. I get to get it out of my head; all the stuff kept in there, without ever putting the pen to paper, and thus clearing my own internal hard drive.

Most of my prose in the accident report was always assuming what the other driver, pedestrian, or cyclist was thinking, or why they did what they did. In true Joe Friday Dragnet form, did I need to hear, “Just the facts, just the facts.” Because this is where my disconnect comes from. To keep it simple, and just report what happened, not what I think happened. I loved the Dispatcher’s reaction to my reports: rolling their eyes and handing it back to me, or their frustration at having no room to sign the report because my words bled over into their section. This was helpful in seeing I needed to cut down the verbiage, and at one point, I realized I should do a rough draft of just the accident description part of the form, and then, after feedback from the dispatcher, rewrite it shorter and simpler, about what actually happened, without all the guesswork about why people did what they did. So, even though I got the answer right away in my first accident class with our instructor, I did appear clueless many years later in reducing the report to the simple actions leading to sideswipe, t-bone, squeeze play, or fixed object. If I could have read other reports, or known the simple food groups of how accidents are classified, I would hopefully have done better, but I am not counting on it!

So have you guessed what the simple answer was and is? Cue Richard Dawson in Family Feud, to say we polled a recent transit operator class and got their best response to, “What does a person say after having a collision or accident?” Answer Is: “I didn’t see you!”

“The car just came out of nowhere.” And blah, blah, blah. So I make sure I am checking side to side, left-right-left, so there is no guesswork about who is encroaching on my lane, my territory. And tracking rate-of-speed is the best way to guess when a motorist is going to make a foolish unsafe move. Impatience can usually be seen a mile a way when sight lines are clear. But in congested, built-up San Francisco, we usually have limited sight distance. Buildings come right up to the corner, or there is almost always a beer truck, bakery truck, or parcel delivery truck parked on the curb or double parked, right up against a crosswalk or corner. And this is where considering, The Bigger You Are, the Harder They Fall, really becomes important. The transit professional has a word for this when this happens: it is called billboarding. You can’t see the forest for the trees, and there is little reaction space to avert a threat that comes from behind the obstacle. Use of the friendly toot, or light flash can be useful, but the bottom line is to adjust by slowing down.

And in the career flow of office politics, it probably doesn’t hurt to employ this idea to your job and duties. No one really knew what I was doing in all the cleaning of the bins in back storerooms, but, tooting one’s horn about getting things done, may be helpful to make sure the right person knows where the credit is due. This can apply towards future job evaluations, and moving up to the bigger office.