One of the differences our corridor streets have that most cities have lost, are the sets of wires over the center of the lanes. Only nine US cities still have overhead from the 50’s. Newer trams recently built may be increasing this number. In SF, we have numerous utility poles alongside the sidewalk that have support wires holding the power. These traveling wires are for our trolleys to be powered by electricity from our hydroelectric grid. Our O’Shaunessy Dam is one valley north of the Yosemite Valley, and provides not only drinking water, but power for our trolleys.

I love the fact that our city uses this carbon free source of power for our extensive trolley lines. We have more miles of trolley wire than any other city in the world. I am proud to work for a railway that has so many different modes of equipment, and that I can call myself a bus driver, but not use any fossil fuels when picking up passengers. I feel as an active agent helping our Earth stay as clean as possible.

Our overhead requires routine maintenance, and it is common to see our big yellow trucks working on the wires over the street. Now, all of our trolleys are equipped with battery power or APU, auxiliary power unit, or EPU, emergency power unit, to go around a crew working on the wires overhead. There are sets of trays of batteries that power this mode. This is another technology change that makes life much easier than in the day when we had to roll around an obstacle or get pushed by another trolley. Gone are the days when passengers would be asked to step outside and help push the bus through an intersection or dead area at a breaker crossing. Before bicycle racks were mounted on the front bumper, we could push a dead-in-the-water trolley from behind with another trolley.

I try to learn about the parts and pieces of the overhead whenever I see the crew taking a break, or just having finished doing a repair. I like to know their terms for things, so if I have to call in a repair, I can at least give Central Control an idea about what I am talking about.

The biggest reason nothing gets done is that the wrong switch or converge is being described on the radio. It is difficult to call in a specific problem in detail when of a driving mind: being in an alert, problem solving state of mind. This is a different part of the brain than that which answers a question about how many number of stops away until a destination, or a part location in a complex intersection of lots of special work. Without knowing the standard name for a part, any report for damage is left open for misunderstanding about where the maintenance is needed. Try as I might, I haven’t been able to convince those outside of training to add this to our syllabus. Line trainers become the key.

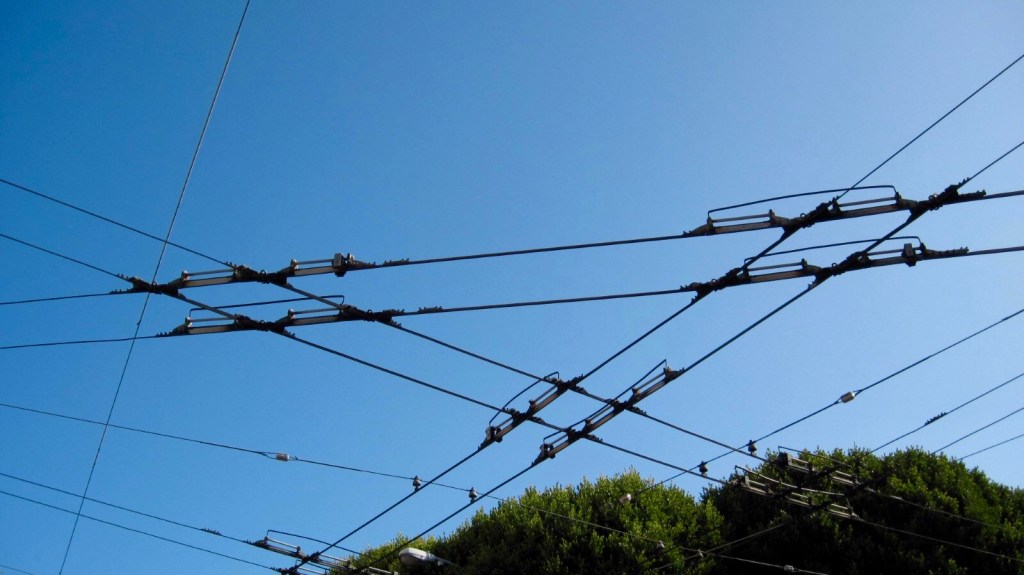

Crossovers

If you ever look up in the middle of an intersection where two trolley lines meet, you will see crossovers. Below these are the fiberglass slots along the traveling wires and jump-over wire bridging the gap, so to speak, over the dead area where the wires cross. This insulates the positive and negative wires from touching one another. We must power off our coach as we coast through this dead area. That is what those yellow dots are that are marked on the street. They mark the dead area where depressing the power pedal has no effect on forward traction. So, if you see dots in the middle of the cross walk, it means we have no power at this point.

Should not the breakers be placed in such a way that there are no dead areas at critical pedestrian and car crossings? Thank you! Now you are beginning to see things from a trolley man’s point of view. The dead area placement is affected by where the power poles are positioned, which has much to do with trees, buildings, and numerous other obstacles. Take time to study an intersection and notice what decisions went in to why things are where they are. Eventually you could graduate to an intersection like Church and Duboce! Or S. Van Ness and Mission! It isn’t as simple as it first might seem. Especially if streets come together at odd angles due to SF’s topography.

Surge Suppressors

On the leading edge of all crossovers is a thing that looks like an Oreo cookie, perpendicular to the wires. This suppresses a spark from a depressed power pedal, should an operator have power on when crossing a breaker. If you have ever been on an electric bus that shudders suddenly, this is because the operator has the power pedal depressed over a breaker. This occurs when trying to move in stopped traffic, especially on an up-hill near a stoplight.

If the dot on the street isn’t measured correctly, or worn away, or unmarked, a jolt can be felt. The surge suppressor reduces this jolt. It is a pair of insulated disks that try to suppress the flash from power attempting to short between the crossing wires. Sometimes these become detached from the wires due to frequent jolts, and this causes trolleys to de-wire near intersections and turns. It took me six months to get the surge suppressor fixed at the Townsend CalTrain crossover for the 45 Union. The glaze in the gaze of an inspector trying to guess what I had described over the radio told me nothing was going to get done. No one in street ops or as a trolley operator knew what a surge suppressor was. This compartmentalization between departments (it’s not my job) in the city is a hassle any small business person understands in trying to get a permit, or pay a fee with the city. Can’t we all get along?

Breakers

Of all crossovers and switches, where opposing poles of electricity cross, is the universal term, breaker. This is all we are required to know as an operator of electric buses. A previous manager of the Overhead Division was asked to create a class plan to instruct new operators on the various parts of the overhead, but he retired before this was put in to play. I try to get the names of the various parts of the overhead when I see the crew on break by a repair area, but this is not easy to do.

Different guys on different crews may call a part by a different name. If I am moving through an area on a bus, or if at a terminal and the crew is busy, it isn’t all that common to get answers to questions about crossover parts and switches. Their general response, “Did you call it in?” Rats. Okay, next time I have a problem in an area, I’ll call it in. But not knowing the name of the part I see in need of repair, makes it a challenge to use this part of my brain while driving. And hence, most operators don’t make the call.

Nothing happens until more than two operators call in a de-wirement problem. So I have to get my leader and follower to also make the call. This is not as easy as it sounds because we no longer see each other at the terminals because recovery time has been cut. Being on a racetrack means that if I want to communicate with my leader or follower, I have to be familiar with where our paths cross. I then have to get their attention, and make sure they can hear me.

One of the first questions asked about inter-bus communication is the necessity to go through the OCC. We can’t contact another bus directly. The best we can do is get the cell phone number of our relief, and make a call at a terminal before relief time to let them know of a delay. Calling Central is the simplest and best way to make contact, and should be the primary method of inter-bus contact. I have seen that “making deals” with another broke-down operator is usually too self-serving and not in the public’s interest. Many times a coaches’ overload in going over a breaker occurs after the bus is hot and been in service for several hours. A bus’ performance changes as the day progresses, and power surges in the breakers have a lot to do with where a bus breaks down.

Dog-bone

In the middle of a converge or diverge are a set of opposing toggles that guide the collectors through a switch to make a smooth transition from one set of wires to another. Their pattern resembles the classic cartoon dog-bone: Two wide flanges at either end with a narrow middle. If they stick, due to changing weather conditions, such as morning dew and fog, I ask for ‘special sauce’ to be applied to reduce sticking.

Sometimes the toggles refuse to change or only go halfway. This causes de-wirements at switches. The problem is the toggles may only act-up intermittently. This can cause a resource drain if an inspector is required to monitor a switch until a de-wirement is observed. As more coaches go through the area and it warms up, a switch may be okay. Or how a previous coach hit the dog-bone can make a difference. Sometimes the de-wirement only occurs after one coach makes a right turn preceding a straight-on coach. Or if a coach has worn shoes, bent collector, or a twisted pole.

If my leader caused the problem the way he or she went through, my follower may have no problem. This creates an awful cat-and- mouse waste of time. Inevitably, the switch needs to be fixed. I say sooner than later, but it isn’t up to me. Only inspectors can make the call. I have learned that even if nothing gets observed or fixed right away, I can relax knowing I did the right thing. Leaving up to ‘God’s time’ is a big resentment I needed to get over as a bus driver. In the mean time, 3 to 5 mph when crossing through special work!

Pan

Above most inductive switches is a sheet metal piece referred to as a pan. This shields the transmitter ball located at the end of the right pole from sending its signal to other switches in the area. When new switches are installed, they were without a pan of metal over them to shield the signal. I went through a two year battle to get pans installed over the inductive ring which is wired to turn the toggles in the switch. Especially at North Point and Van Ness. After countless de-wirements, pans were installed. It is this poverty consciousness that pervades most government agencies, transportation notwithstanding. Waiting for failure is the watchword for trolley repair and overhead repair and it is another battle in my head that I have to let go if I am to stay safe. People ask me why I am writing this book, and this could be my number one reason. I can’t change the system, but I can change myself. And this changes the impression I am creating when behind the wheel of that large automobile. How did I get here? Sounds like Talking Heads, no? The new doughnuts are white and are not necessarily installed with a pan on top. Only after months or years of calls do they get a pan that shields the signal from another trolley. Cue Bob Dylan’s “Blowin in the Wind,” as to when the switch will be installed properly.

Truth be told, some switches activate for no apparent reason. No matter how meticulous a pan is installed to shield a nearby trolley coach from inadvertent trigger, switches activate on their own. I have looked at my switch control dial in the normal position, only to see that the semaphore has changed, or I hear the click of the switch changing, even before I am over the doughnut. As a Line Trainer, this is a mandatory lesson about what makes a trolley operator different from a motor coach operator: we must listen to what the overhead is telling us: especially when we need to turn on a switch.

Fortunately, I am always aware of what position the switch is in before I cross the intersection. I have not brought down any overhead due to a falsely triggered switch. As a line trainer, I tell my student where these ghosts are in the system. A study of the natural Earth energy lines does make for a compelling reason as to why these electrical mysteries keep happening.

Doughnut

Underneath the pan is the doughnut. This is the electromagnetic loop that sends the turn signal message from our foot pedal button on the floor to the switch. In certain areas, such as Main and Mission, Mission and 30th, and Market and Eighth, a following trolley must not activate a turn signal until the lead coach has passed the frog of the switch. By reactivating the toggles before the lead coach passes, this causes the lead coach to switch incorrectly.

I am good at spotting this, and because my follower is in a rush, he has to then reset his poles because now the switch is set in the wrong direction because he passed the doughnut, and the lead coach took the switch. The distance between the doughnut and switch is too far away and more than one trolley can pause between the transmitter and the diverge. Anyway, I haven’t heard of anyone getting in trouble for this, but I think that they should. Call me Mister Overhead. If following the one block spacing rule, these de-wirements would not occur.

The newer trolleys have a smaller footprint on the wires. The brasserie is smaller and the carbons are thinner. The poles are two feet longer. Less metal is used, and parts are more flexible. To be fair, these improvements have helped tremendously. New switches seem to have less problems, and all trolleys can get around a repair area using battery power. These changes have made for a nicer day behind the wheel.

Selectric Switch

If you look up near an intersection of two trolley lines, you may see two staggered parallel gray boxes before the converge of two sets of wires. These are selectric switches. They are triggered by the angle of the dangle. When a coach begins a turn, the poles begin to skew on track and are no longer parallel on the wires. The angle of the bus, with the poles askew, triggers the switch because the gray boxes are hit simultaneously by the angled poles. If you stand by such a corner, you can hear the click as a trolley makes a turn on to another line. Being in a Zen state means being able to hear the click!